Encouraging developments in worker awareness as ‘Together For Decent Leather’ project concludes

How does state-sponsored health insurance help a shoe factory worker in Tamil Nadu’s Ambur? It could prevent the worker from falling into a debt trap while raising funds for a medical emergency. Though factories of Ambur, which is South India’s biggest leather manufacturing cluster, supply for high-end global brands, they pay their workers grossly insufficient wages, sometimes lower than the bare minimum (below Rs. 10,000 p.m).

Not many workers are aware of their claims under statutory benefits like the Employee State Insurance (ESI) that could go a long way in easing financial burdens. And that’s why it was surprising to see a group of workers from Ambur come together a few months ago to demand their rights. With the assistance of local activists and CSOs, they submitted a memorandum to the local taluk office asking ESI facilities (offices and dispensaries) to be extended to all parts of Tirupattur district and for a district-level speciality hospital to treat occupational health problems. The intervention helped and soon, the ESI department extended the facilities and sanctioned a dispensary in the area, recalls Kohila Senbagam, Project Coordinator (Leather sector).

Kohila says that the workers’ mobilization played a big role in this remarkable development. And this gathered momentum after the awareness creation done by the local Cividep team. ‘We were able to talk about ESI and other rights in detail to the workers as part of the Together for Decent Leather project, which concluded recently,’ she says.

Focussed Interventions Help

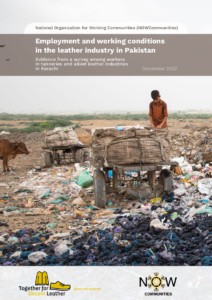

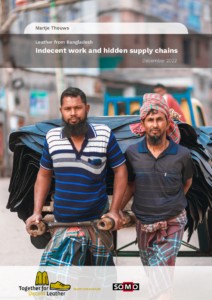

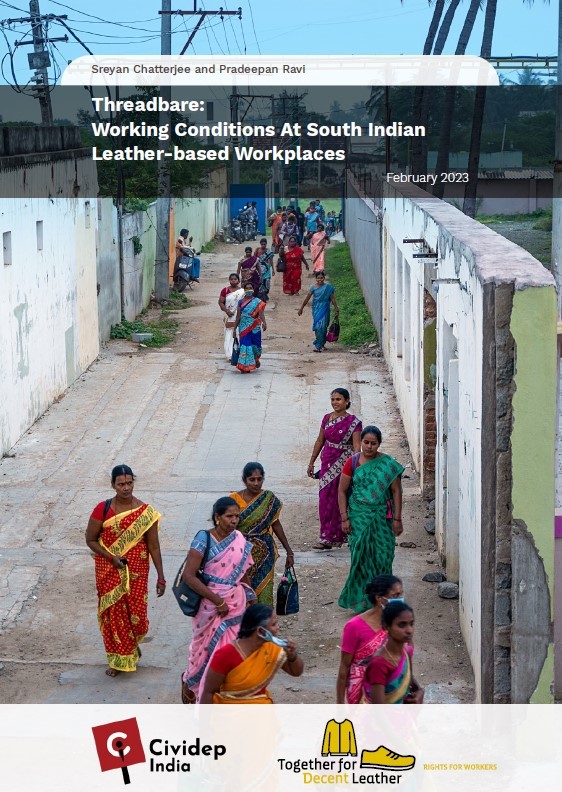

The Together for Decent Leather project, initiated in 2020, is a multi-country civil society consortium striving to improve working conditions in global leather supply chains across South Asia. The project comes to a close this year, after three years of collaborative work across partners in India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Netherlands, Austria, and Germany.

Kohila and Cividep Program Lead Pradeepan Ravi have been at the helm of leather sector activities, since 2016. They say that more workers now know about worker rights, statutory benefits, and have developed leadership skills through Cividep’s training sessions. “Shoe factory workers protested when there was an instance of sexual harassment by a supervisor. The person was dismissed,” says Kohila.

Homeworkers (as seen in the pic above) too are now motivated to stand up for their rights. “They recently demanded that the village Gram Sabha (village council) formally recognise the local homeworkers’ collective,” says Pradeepan. Further, they collectively refused to take work from a subcontractor who was paying very low piece rates. “The project really helped workers experience the benefits of solidarity,” he says.

Through the project, Cividep has been able to reach out to more than 1000 workers (factory, homeworker and tannery) through training programs, health camps, and social security assistance. Additionally, a health and safety handbook has been designed in Tamil for leather homeworkers and tannery workers.

Read more on Cividep’s website

You can download Cividep’s Handbooks here:

Homeworker’s handbook on occupational health and safety (English version)

Homeworker’s handbook on occupational health and safety (Tamil version)

Suedwind, Inkota

Suedwind, Inkota

INKOTA/Südwind Austria

INKOTA/Südwind Austria

SOMO

SOMO

Insiya Syed

Insiya Syed